Nitrogen narcosis

| Inert gas narcosis [Nitrogen narcosis] |

|

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Divers breathe a mixture of oxygen, helium and nitrogen for deep dives to avoid the effects of narcosis. A cylinder label shows the maximum operating depth and mixture (oxygen/helium). |

|

| DiseasesDB | 30088 |

| MeSH | C21.613.455.571 |

| Some components of breathing gases, and their relative narcotic potentcies[1] | |

| Gas | Relative narcotic potency |

|---|---|

| Ne | 0.3 |

| H2 | 0.6 |

| N2 | 1.0 |

| O2 | 1.7 |

| Ar | 2.3 |

| Kr | 7.1 |

| CO2 | 20.0 |

| Xe | 25.6 |

Narcosis while diving (also known as nitrogen narcosis, inert gas narcosis, raptures of the deep, Martini effect), is a reversible alteration in consciousness that occurs while scuba diving at depth. The Greek word ναρκωσις (narcosis) is derived from narke, "temporary decline or loss of senses and movement, numbness", a term used by Homer and Hippocrates.[2] Narcosis produces a state similar to alcohol intoxication or nitrous oxide inhalation, and can occur during shallow dives, but usually does not become noticeable until greater depths, beyond 30 meters (100 ft).

Apart from helium, and probably neon, all gases that can be breathed have a narcotic effect, which is greater as the lipid solubility of the gas increases.[3] As depth increases, the effects may become hazardous as the diver is increasingly impaired. Although divers can learn to cope with the effects, it is not possible to develop a tolerance. While narcosis affects all divers, predicting the depth at which narcosis will affect a diver is difficult, as susceptibility varies widely from dive to dive and amongst individuals.

The condition is completely reversed by ascending to a shallower depth with no long-term effects. For this reason, narcosis while diving in open water rarely develops into a serious problem as long as the divers are aware of its symptoms and ascend to manage it. Diving beyond 40 m (130 ft) is considered outside the scope of recreational diving: as narcosis and oxygen toxicity become critical factors, specialist training is required in the use of various gas mixtures such as trimix or heliox.

Contents |

Classification

Narcosis results from breathing gases under elevated pressure and may be classified by the principal gas involved. The noble gases, except helium and probably neon,[3] as well as nitrogen, oxygen and hydrogen cause a decrement in mental function, but their effect on psychomotor function (processes affecting the coordination of sensory or cognitive processes and motor activity) varies widely. The effects of carbon dioxide consistently result in a decrease of both mental and psychomotor function.[4] The noble gases argon, krypton, and xenon are more narcotic than nitrogen at a given pressure, and xenon has so much anesthetic activity that it is actually a usable anesthetic at 80% concentration and normal atmospheric pressure. Xenon has historically been too expensive to be used very much in practice, but it has been successfully used for surgical operations, and xenon anesthesia systems are still being proposed and designed.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Due to its perception-altering effects, the onset of narcosis may be hard to recognize.[6][7] At its most benign, narcosis results in relief of anxiety and a feeling of tranquility and mastery of the environment. These effects are essentially identical to various concentrations of nitrous oxide. They also resemble (though not as closely) the effects of alcohol and the familiar benzodiazepine drugs such as diazepam and alprazolam.[8] Such effects are not harmful unless they cause some immediate danger not to be recognized and addressed. Once stabilized, the effects generally remain the same at a given depth, only worsening if the diver ventures deeper.[9]

The most dangerous aspects of narcosis are the loss of decision-making ability and focus, and impaired judgment, multi-tasking and coordination. Other effects include vertigo, tingling and numbness of the lips, mouth and fingers, and exhaustion. The syndrome may cause exhilaration, giddiness, extreme anxiety, depression, or paranoia, depending on the individual diver and the diver's medical or personal history. When more serious, the diver may begin to feel invulnerable, disregarding normal safe diving practices.

The relation of depth to narcosis is sometimes informally known as "Martini's law". This is the idea that narcosis results in the feeling of one martini for every 10 m (33 ft) below 20 m (66 ft) depth. This is a very rough guide, and not a substitute for an individual diver's known susceptibility, or for standard diving safety guides. Professional divers use such a calculation only as a rough guide to give new divers a metaphor, comparing a situation they may be more familiar with.[10]

Reported signs and symptoms are summarized against typical depths in meters and feet of sea water in the following table:[11]

| Pressure (bar) | Depth (m) | Depth (ft) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 0–10 | 0-33 | Unnoticeable small symptoms, or no symptoms at all. |

| 2–4 | 10–30 | 33–100 | Mild impairment of performance of unpracticed tasks. Mildly impaired reasoning. Mild euphoria possible. |

| 4–6 | 30–50 | 100–165 | Delayed response to visual and auditory stimuli. Reasoning and immediate memory affected more than motor coordination. Calculation errors and wrong choices. Idea fixation. Over-confidence and sense of well-being. Laughter and loquacity (in chambers) which may be overcome by self control. Anxiety (common in cold murky water). |

| 6–8 | 50–70 | 165–230 | Sleepiness, impaired judgment, confusion. Hallucinations. Severe delay in response to signals, instructions and other stimuli. Occasional dizziness. Uncontrolled laughter, hysteria (in chamber). Terror in some. |

| 8–10 | 70–90 | 230–300 | Poor concentration and mental confusion. Stupefaction with some decrease in dexterity and judgment. Loss of memory, increased excitability. |

| 10+ | 90+ | 300+ | Hallucinations. Increased intensity of vision and hearing. Sense of impending blackout, euphoria, dizziness, manic or depressive states, a sense of levitation, disorganization of the sense of time, changes in facial appearance. Unconsciousness. Death. |

Causes

The cause of narcosis is related to the increased solubility of gases in body tissues, as a result of the elevated pressures at depth (Henry's law).[12] Modern theories have suggested that inert gases dissolving in the lipid bilayer of cell membranes cause narcosis.[13] More recently, researchers have been looking at neurotransmitter receptor protein mechanisms as a possible cause of the narcosis.[14] The breathing gas mix entering the diver's lungs will have the same pressure as the surrounding water, known as the ambient pressure. For any given depth, the pressure of gases in the blood passing through the brain catches up with ambient pressure within a minute or two and this produces a delay in narcotic effect after coming to a new depth.[6][15] Rapid compression potentiates narcosis, owing to carbon dioxide retention.[16][17]

A divers' cognition may be affected on dives as shallow as 10 m (33 ft), but the changes are not usually noticeable.[18] However there is no reliable method to predict the depth at which narcosis becomes noticeable, or the severity of the effect on an individual diver, as the effect may vary from dive to dive (even on the same day).[6][17]

Significant impairment due to narcosis is an increasing risk below depths of about 30 m (100 ft), corresponding to an ambient pressure of about 4 bar (400 kPa).[6] Most sport scuba training organizations recommend depths of no more than 40 m (130 ft) because of risk of narcosis.[10] When breathing air at depths of 90 m (300 ft)—an ambient pressure of about 10 bar (1,000 kPa)—narcosis in most divers leads to hallucinations, loss of memory, and unconsciousness.[16][19] A number of divers have died in attempts to set air depth records below 120 m (400 ft). Because of these incidents, the Guinness Book of World Records no longer reports on this figure.[20]

Narcosis has been compared with altitude sickness insofar as its variability (though not its symptoms); its effects depend on many factors, with variations between individuals. Thermal cold, stress, heavy work, fatigue, and carbon dioxide retention all increase the risk and severity of narcosis.[4][6]

Narcosis is known to be additive to even minimal alcohol intoxication,[21][22] and also to the effects of other drugs such as marijuana (which is more likely than alcohol to have effects which last into a day of abstinence from use).[23] Other sedative and analgesic drugs, such as opiate narcotics and benzodiazepines, add to narcosis.[21]

Mechanism

The precise mechanism is not well understood, but it appears to be the direct effect of gas dissolving into nerve membranes and causing temporary disruption in nerve transmissions. While the effect was first observed with air, other gases including argon, krypton and hydrogen cause very similar effects at higher than atmospheric pressure.[24] Some of these effects may be due to antagonism at NMDA receptors and potentiation of GABAA receptors,[25] similar to the mechanism of nonpolar anesthetics such diethyl ether or ethylene.[26] However, their reproduction by the very chemically inactive gas argon makes them unlikely to be a strictly chemical bonding to receptors in the usual sense of a chemical bond. An indirect physical effect—such as a change in membrane volume—would therefore be needed to affect the ligand-gated ion channels of nerve cells.[27] Trudell et al. have suggested non-chemical binding due to the attractive van der Waals force between proteins and inert gases.[28]

Similar to the mechanism of ethanol's effect, the increase of gas dissolved in nerve cell membranes may cause altered ion permeability properties of the neural cells' lipid bilayers. The partial pressure of a gas required to cause a measured degree of impairment correlates well with the lipid solubility of the gas: the greater the solubility, the less partial pressure is needed.[27]

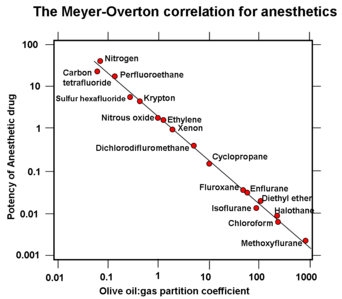

An early theory, the Meyer-Overton hypothesis suggested that narcosis happens when the gas penetrates the lipids of the brain's nerve cells, causing direct mechanical interference with the transmission of signals from one nerve cell to another.[12][13][17] More recently, specific types of chemically-gated receptors in nerve cells have been identified as being involved with anesthesia and narcosis. However, the basic and most general underlying idea, that nerve transmission is altered in many diffuse areas of the brain as a result of gas molecules dissolved in the nerve cells' fatty membranes, remains largely unchallenged.[14][29]

Diagnosis and management

The symptoms described may be caused by other factors during a dive: ear problems causing disorientation or nausea;[30] early signs of oxygen toxicity causing visual disturbances;[31] or hypothermia causing rapid breathing and shivering.[32] Nevertheless the presence of any of these symptoms should imply narcosis. Alleviation of the effects upon ascending to a shallower depth will confirm the diagnosis. Given the setting, other likely conditions do not produce reversible effects. In the rare event of misdiagnosis when another condition is causing the symptoms, the initial management—ascending closer to the surface—is still essential.[7]

The management of narcosis is simply to ascend to shallower depths; the effects then disappear within minutes.[33] In the event of complications or other conditions being present, ascending is always the correct initial response. Should problems remain, then it is necessary to abort the dive. The decompression schedule can still be followed unless other conditions require emergency assistance.[34]

Prevention

The most straightforward way to avoid nitrogen narcosis is for a diver to limit the depth of dives. If narcosis does occur, the effects disappear almost immediately upon ascending to a shallower depth. Since narcosis becomes more severe as depth increases, a diver keeping to shallower depths can avoid serious narcosis. Most recreational dive schools will only certify basic divers to depths of 18 m (60 ft), and at these depths narcosis does not present a large risk. Further training is normally required for certification up to 30 m (100 ft) on air, and this training should include a discussion of narcosis, its effects, and cure. Some diver training agencies offer specialty training to prepare recreational divers to go to depths of 40 m (130 ft), often consisting of further theory and some practice in deep dives with close supervision.[35][nb 1] Scuba organizations which train for diving beyond recreational depths,[nb 2] may forbid diving with gases that cause too much narcosis at depth in the average diver, and strongly encourage the use of other breathing gas mixes containing helium in place of some or all of the nitrogen in air—such as trimix and heliox—because helium has no narcotic potential.[3][36] The use of these gases forms part of technical diving and requires further training and certification.[10]

While the individual diver cannot predict exactly at what depth the onset of narcosis will occur on a given day, the first symptoms of narcosis for any given diver are often more predictable and personal. For example, one diver may have trouble with eye focus (close accommodation for middle-aged divers), another may experience feelings of euphoria, and another feelings of claustrophobia. Some divers report that they have hearing changes, and that the sound which their exhaled bubbles make becomes different. Specialist training may help divers in identifying these personal onset signs, and these may then be used as a signal to ascend to shallower depths. Although severe narcosis may interfere with the judgment necessary to take preventive action, a diver who remains calm and is alert to the danger will be capable of resolving these problems at an earlier stage.[33]

Deep dives should be made only after a gradual training to gradually test the individual diver's sensitivity to increasing depths, with careful supervision and logging of reactions. Diving organizations such as Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) emphasize that such sessions are for the purpose of gaining experience in recognizing the onset symptoms of narcosis for an individual, which are somewhat more repeatable than for the average group of divers. Scientific evidence does not show that a diver can train to overcome any measure of narcosis at a given depth or become tolerant of it.[37]

Equivalent narcotic depth (END) is a commonly used way of expressing the narcotic effect of different breathing gases.[38] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Diving Manual now states that both oxygen and nitrogen should be considered equally narcotic.[39] Standard tables, based on relative lipid solubilities, list conversion factors for narcotic effect of other gases.[40] For example, neon at a given pressure has a narcotic effect equivalent to nitrogen at 0.28 times that pressure, so in principle it should be usable at nearly four times the depth. Argon, however, has 2.33 times the narcotic effect of nitrogen, and is not suitable as a breathing gas for diving (it is used as a drysuit inflation gas, owing to its low thermal conductivity). Some gases have other dangerous effects when breathed at pressure; for example, high-pressure oxygen can lead to oxygen toxicity. Although helium is the least intoxicating of the breathing gases, at greater depths it can cause high pressure nervous syndrome, a still-mysterious but apparently unrelated phenomenon.[41] Inert gas narcosis is only one factor which influences the choice of gas mixture; the risks of decompression sickness and oxygen toxicity, cost, and other factors are also important.[42]

Because of similar and additive effects, divers should avoid sedating medications and drugs, such as marijuana and alcohol before any dive. A hangover, combined with the reduced physical capacity that goes with it, makes nitrogen narcosis more likely.[21] Experts recommend total abstinence from alcohol at least 12 hours before diving, and longer for other drugs.[43] Abstinence time needed for marijuana is unknown, but due to the much longer half-life of the active agent of this drug in the body, it is likely to be longer than for alcohol.[23]

Prognosis and epidemiology

Narcosis is potentially one of the most dangerous conditions to affect the scuba diver below about 30 m (100 ft). Except for occasional amnesia of events at depth, the effects of narcosis are entirely reversible by ascending and therefore pose no problem in themselves, even for repeated, chronic or acute exposure.[6][17] Nevertheless, the severity of narcosis is unpredictable and it can be fatal while diving, as the result of illogical behavior in a dangerous environment.[17]

Tests have shown that all divers are affected by nitrogen narcosis, though some are less affected than others. Even though it is possible that some divers can manage better than others because of learning to cope with the subjective impairment, the underlying behavioral effects remain.[26][44][45] These effects are particularly dangerous because a diver may feel they are not experiencing narcosis, yet still be affected by it.[6]

History

French researcher Victor T. Junod was the first to describe symptoms of narcosis in 1834, noting "the functions of the brain are activated, imagination is lively, thoughts have a peculiar charm and, in some persons, symptoms of intoxication are present."[46][47] Junod suggested that narcosis resulted from pressure causing increased blood flow and hence stimulating nerve centers.[48] Walter Moxon (1836–1886), a prominent Victorian physician, hypothesized in 1881 that pressure forced blood to inaccessible parts of the body and the stagnant blood then resulted in emotional changes.[49] The first report of anesthetic potency being related to lipid solubility was published by Hans H. Meyer in 1899, entitled Zur Theorie der Alkoholnarkose. Two years later a similar theory was published independently by Charles Ernest Overton.[50] What became known as the Meyer-Overton Hypothesis is illustrated in the diagram to the right.

In 1939, Albert R. Behnke and O. D. Yarborough demonstrated that gases other than nitrogen also could cause narcosis.[51] For an inert gas the narcotic potency was found to be proportional to its lipid solubility. As hydrogen has only 0.55 the solubility of nitrogen, deep diving experiments using hydrox were conducted by Arne Zetterström between 1943 and 1945.[52] Jacques-Yves Cousteau in 1953 famously described it as "l’ivresse des grandes profondeurs" or the "rapture of the deep".[53]

Further research into the possible mechanisms of narcosis by anesthetic action led to the "minimum alveolar concentration" concept in 1965. This measures the relative concentration of different gases required to prevent motor response in 50% of subjects in response to stimulus, and shows similar results for anesthetic potency as the measurements of lipid solubility.[54] The (NOAA) Diving Manual was revised to recommend treating oxygen as if it were as narcotic as nitrogen, following research by Christian J. Lambertsen et al. in 1977 and 1978.[55]

See also

- Hydrogen narcosis

Footnotes

References

- ↑ Bennett, Peter; Rostain, Jean Claude (2003). "Inert Gas Narcosis". In Brubakk, Alf O; Neuman, Tom S. Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving (5th ed.). United States: Saunders Ltd. p. 304. ISBN 0702025712. OCLC 51607923. (Value for Krypton from 4th Edition, p. 176).

- ↑ Askitopoulou, Helen; Ramoutsaki, Ioanna A; Konsolaki, Eleni (April 12, 2000). "Etymology and Literary History of Related Greek Words". Analgesia and Anesthesia. International Anesthesia Research Society. http://www.anesthesiaanalgesia.org/content/91/2/486.full. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Brubakk & Neuman 2003, p. 305

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hesser, CM; Fagraeus, L; Adolfson, J (1978). "Roles of nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide in compressed-air narcosis". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine (Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, Inc) 5 (4): 391–400. ISSN 0093-5387. OCLC 2068005. PMID 734806. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/2810. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ Burov, NE; Kornienko, Liu; Makeev, GN; Potapov, VN (November–December 1999). "Clinical and experimental study of xenon anesthesia". Anesteziol Reanimatol (6): 56–60. http://www.general-anaesthesia.com/xenon-anaesthesia.html. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Brubakk & Neuman 2003, p. 301

- ↑ 7.0 7.1

- ↑ Hobbs M (2008). "Subjective and behavioural responses to nitrogen narcosis and alcohol". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine : Journal of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, Inc 35 (3): 175–84. PMID 18619113. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/8101. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ Lippmann, John; Mitchell, Simon J (2005). "Nitrogen narcosis". Deeper into Diving (2nd ed.). Victoria, Australia: J.L. Publications. p. 103. ISBN 097522901X. OCLC 66524750.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Brylske, A (2006). Encyclopedia of Recreational Diving (3rd ed.). United States: Professional Association of Diving Instructors. ISBN 1878663011.

- ↑ Lippmann & Mitchell 2005, p. 105

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Brubakk & Neuman 2003, p. 308

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Paton, William (1975). "Diver narcosis, from man to cell membrane". Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society (first published at Oceans 2000 Conference) 5 (2). http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/5897. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rostain, Jean C; Balon N (2006). "Recent neurochemical basis of inert gas narcosis and pressure effects". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine 33 (3): 197–204. PMID 16869533. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/5060. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ Case, EM; Haldane, John Burdon Sanderson (1941). "Human physiology under high pressure". Journal of Hygiene 41 (3): 225–49. doi:10.1017/S0022172400012432. PMID 20475589.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Brubakk & Neuman 2003, p. 303

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Hamilton, RW; Kizer, KW (eds) (1985). "Nitrogen Narcosis". 29th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop (Bethesda, MD: Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society) (UHMS Publication Number 64WS(NN)4-26-85). http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/4496. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ Petri, NM (2003). "Change in strategy of solving psychological tests: evidence of nitrogen narcosis in shallow air-diving". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine (Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, Inc) 30 (4): 293–303. PMID 14756232. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3976. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ Hill, Leonard; David, RH; Selby, RP; et al. (1933). "Deep diving and ordinary diving". Report of a Committee Appointed by the British Admiralty.

- ↑ PSAI Philippines. "Professional Scuba Association International History". Professional Scuba Association International - Philippines. http://www.psai-philippines.com/history.html. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Fowler, B; Hamilton, K; Porlier, G (1986). "Effects of ethanol and amphetamine on inert gas narcosis in humans". Undersea Biomedical Research 13 (3): 345–54. PMID 3775969. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3050. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ Michalodimitrakis, E; Patsalis, A (1987). "Nitrogen narcosis and alcohol consumption--a scuba diving fatality". Journal of Forensic Sciences 32 (4): 1095–7. PMID 3612064.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Pope, Harrison G; Gruber, Amanda J; Hudson, James I; Huestis, Marilyn A; Yurgelun-Todd, Deborah (2001). "Neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users". Archives of General Psychiatry (American Medical Association) 58 (10): 909–15. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.909. PMID 11576028. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/58/10/909. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Brubakk & Neuman 2003, p. 304

- ↑ Hapfelmeier, Gerhard; Zieglgänsberger, Walter; Haseneder, Rainer; Schneck, Hajo; Kochs, Eberhard (December 2000). "Nitrous oxide and xenon increase the efficacy of GABA at recombinant mammalian GABA(A) receptors". Anesthesia and Analgesia 91 (6): 1542–9. doi:10.1097/00000539-200012000-00045. PMID 11094015. http://www.anesthesia-analgesia.org/cgi/content/full/91/6/1542. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hamilton, K; Laliberté, MF; Fowler, B (1995). "Dissociation of the behavioral and subjective components of nitrogen narcosis and diver adaptation". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine : Journal of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society 22 (1): 41–9. ISSN 1066-2936. OCLC 26915585. PMID 7742709. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/2199. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Franks, NP; Lieb, WR (1994). "Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anaesthesia". Nature 367 (6464): 607–14. doi:10.1038/367607a0. PMID 7509043.

- ↑ Trudell, JR; Koblin, DD; Eger, EI (1998). "A molecular description of how noble gases and nitrogen bind to a model site of anesthetic action". Anesthesia and Analgesia 87 (2): 411–8. doi:10.1097/00000539-199808000-00034. PMID 9706942. http://www.anesthesia-analgesia.org/cgi/content/abstract/87/2/411. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ↑ Smith, EB (July 1987). "Priestley lecture 1986. On the science of deep-sea diving--observations on the respiration of different kinds of air". Undersea & hyperbaric medicine : journal of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, Inc 14 (4): 347–69. PMID 3307084. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/2720. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ Molvaer, Otto I (2003). "Otorhinolaryngological aspects of diving". In Brubakk, Alf O; Neuman, Tom S. Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving (5th ed.). United States: Saunders Ltd. p. 234. ISBN 0702025712. OCLC 51607923.

- ↑ Clark, James M; Thom, Stephen R (2003). "Oxygen under pressure". In Brubakk, Alf O; Neuman, Tom S. Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving (5th ed.). United States: Saunders Ltd. p. 374. ISBN 0702025712. OCLC 51607923.

- ↑ Mekjavic, Igor B; Tipton, Michael J; Eiken, Ola (2003). "Thermal considerations in diving". In Brubakk, Alf O; Neuman, Tom S. Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving (5th ed.). United States: Saunders Ltd. p. 129. ISBN 0702025712. OCLC 51607923.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Lippmann & Mitchell 2005, p. 106

- ↑ U.S. Navy Diving Manual 2008, vol. 2, ch. 9, p. 35–46

- ↑ "Extended Range Diver". International Training. 2009. http://www.tdisdi.com/index.php?did=80&site=2. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ Hamilton Jr, RW; Schreiner, HR (eds) (1975). "Development of Decompression Procedures for Depths in Excess of 400 feet". 9th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop (Bethesda, MD: Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society) (UHMS Publication Number WS2-28-76): 272. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/4498. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ Hamilton, K; Laliberté, MF; Heslegrave, R (1992). "Subjective and behavioral effects associated with repeated exposure to narcosis". Aviation, space, and environmental medicine 63 (10): 865–9. PMID 1417647.

- ↑ IANTD (1 January 2009). "IANTD Scuba & CCR, PSCR & SCR Rebreather Diver Programs (Recreational Trimix Diver)". IANTD/IAND, Inc. http://www.iantd.com/iantd3.html. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ↑ "Mixed-Gas & Oxygen". NOAA Diving Manual, Diving for Science and Technology. 4th. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2002. "[16.3.1.2.4] ... since oxygen has some narcotic properties, it is appropriate to include the oxygen in the END calculation when using trimixes (Lambersten et al. 1977,1978). The non-helium portion (i.e., the sum of the oxygen and the nitrogen) is to be regarded as having the same narcotic potency as an equivalent partial pressure of nitrogen in air, regardless of the proportions of oxygen and nitrogen."

- ↑ Anttila, Matti. "Narcotic factors of gases". http://www.techdiver.ws/exotic_gases.shtml#6. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ Bennett, Peter; Rostain, Jean Claude (2003). "The High Pressure Nervous Syndrome". In Brubakk, Alf O; Neuman, Tom S. Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving (5th ed.). United States: Saunders Ltd.. pp. 323–57. ISBN 0702025712. OCLC 51607923.

- ↑ Lippmann & Mitchell 2005, pp. 430–1

- ↑ St Leger Dowse, Marguerite (2008). "Diving Officer's Conference presentations". British Sub-Aqua Club. http://www.bsac.com/page.asp?section=2595§ionTitle=DOC+presentation+summaries&preview=1. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ Fowler, B; Ackles, KN; Porlier, G (1985). "Effects of inert gas narcosis on behavior--a critical review.". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine : Journal of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society 12 (4): 369–402. ISSN 0093-5387. OCLC 2068005. PMID 4082343. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3019. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ Rogers, WH; Moeller, G (1989). "Effect of brief, repeated hyperbaric exposures on susceptibility to nitrogen narcosis". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine : Journal of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society 16 (3): 227–32. ISSN 0093-5387. OCLC 2068005. PMID 2741255. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/2522. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ Brubakk & Neuman 2003, p. 300

- ↑ Junod, Victor T (1834). "Recherches physiologiques et thérapeutiques sur les effets de la compression et de la raréfaction de l'air". Revue médicale française et étrangère: journal des progrès de la médecine hippocratique (Chez Gabon et compagnie): 350–368. http://books.google.com/?id=K5XREXyDSQoC. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ↑ Brubakk & Neuman 2003, p. 306

- ↑ Moxon, Walter (1881). "Croonian lectures on the influence of the circulation on the nervous system". British Medical Journal 1: 491–7, 583–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1057.491. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a789031692~db=all. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ↑ Overton, Charles Ernest (1901). "Studien Über Die Narkose" (in German). Allgemeiner Pharmakologie (Institut für Pharmakologie).

- ↑ Behnke, AR; Yarborough, OD (1939). "Respiratory resistance, oil-water solubility and mental effects of argon compared with helium and nitrogen". American Journal of Physiology (126): 409–15.

- ↑ Ornhagen, H (1984). "Hydrogen-Oxygen (Hydrox) breathing at 1.3 MPa". FOA Rapport C58015-H1 (Stockholm: National Defence Research Institute). ISSN 0347-7665.

- ↑ Cousteau, Jacques-Yves; Dumas, Frédéric (1953). The Silent World: A Story of Undersea Discovery and Adventure. Harper & Brothers Publishers. pp. 266. ISBN 0792267966.

- ↑ Eger, EI; Saidman, LJ; Brandstater, B (1965). "Minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration: a standard of anesthetic potency". Anesthesiology 26 (6): 756–63. doi:10.1097/00000542-196511000-00010. PMID 5844267.

- ↑ Lambertsen, Christian J; Gelfand, R; Clark, JM (1978). "University of Pennsylvania Institute for Environmental Medicine report, 1978". University of Pennsylvania. Institute for Environmental Medicine. http://archives.mc.duke.edu/uhmsupiemr.html. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

External links

- Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Scientific body, publications about nitrogen narcosis.

- Rubicon Research Repository Searchable repository of Diving and Environmental Physiology Research.

- Diving Diseases Research Centre (DDRC) UK charity dedicated to treatment of diving diseases.

- Campbell, Ernest S. (2009-06-25). "Diving While Using Marijuana". http://scuba-doc.com/marij.html. Retrieved 2009-08-25. ScubaDoc's overview of marijuana and diving.

- Campbell, Ernest S. (2009-05-03). "Alcohol and Diving". http://scuba-doc.com/alch.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-25. ScubaDoc's overview of alcohol and diving.

- Campbell, George D. (2009-02-01). "Nitrogen Narcosis". Diving with Deep-Six. http://www.deep-six.com/page74.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-25.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||